Note: Here is roughly what I said during my presentation at Digital Humanities 2008 in Oulu, Finland (or at least meant to say—I was so sleep deprived thanks to the unceasing sunshine that I’m not sure what I actually did say). My session, which explored the meaning and significance of “digital humanities,” also featured rich, engaging presentations by Edward Vanhoutte on the history of humanities computing and John Walsh on comparing alchemy and digital humanities. My presentation reports on my project to remix my dissertation as a work of digital scholarship and synthesizes many of my earlier blog posts to offer a sort of Reader’s Digest condensed version of my blog for the past 7 months. By the way, sorry that I’ve been away from the blog for so long. I’ve spent the last month and a half researching and writing a 100 page report on archival management software, reviewing essays, performing various other professional duties, and going on both a family vacation to San Antonio and a grown-up vacation to Portland, OR (vegan meals followed up by Cap’n Crunch donuts. It took me a week to recover from the donut hangover). In the meantime, lots of ideas have been brewing, so expect many new blog entries soon.

***

When I began working on my dissertation in the mid 1990s, I used a computer primarily to do word processing—and goof off with Tetris. Although I used digital collections such as Early American Fiction and Making of America for my dissertation project on bachelorhood in 19th C American literature, I did much of my research the old fashioned way: flipping through the yellowing pages of 19th century periodicals on the hunt for references to bachelors, taking notes using my lucky leaky fountain pen. I relied on books for my research and, in the end, produced a book.

At the same time that I was dissertating, I was also becoming enthralled by the potential of digital scholarship through my work at the University of Virginia’s (late lamented) Electronic Text Center. I produced an electronic edition of the first section from Donald Grant Mitchell’s bestseller Reveries of a Bachelor that allowed readers to toggle between variants. I even convinced my department to count Perl as a second language, citing the Matt Kirschenbaum precedent (“come on, you let Matt do it, and look how well that turned out”) and the value of computer languages to my profession as a budding digital humanist. However, I decided not to create an electronic version of my dissertation (beyond a carefully backed-up Word file) or to use computational methods in doing my research, since I wanted to finish the darn thing before I reached retirement age.

Last year, five years after I received my PhD and seven years after I had become the director of Rice University’s Digital Media Center, I was pondering the potential of digital humanities, especially given mass digitization projects and the emergence of tools such as TAPOR and Zotero. I wondered: What is digital scholarship, anyway? What does it take to produce digital scholarship? What kind of digital resources and tools are available to support it? To what extent do these resources and tools enable us to do research more productively and creatively? What new questions do these tools and resources enable us to ask? What’s challenging about producing digital scholarship? What happens when scholars share research openly through blogs, institutional repositories, & other means?

I decided to investigate these questions by remixing my 2002 dissertation as a work of digital scholarship. Now I’ll acknowledge that my study is not exactly scientific—there is a rather subjective sample of one. However, I figured, somewhat pragmatically, that the best way for me to understand what digital scholars face was to do the work myself. I set some loose guidelines: I would rely on digital collections as much as possible and would experiment with tools for analyzing, annotating, organizing, comparing and visualizing digital information. I would also explore different ways of representing my ideas, such as hypertextual essays and videos. Embracing social scholarship, I would do my best to share my work openly and make my research process transparent. So that the project would be fun and evolve organically, I decided to follow my curiosity wherever it led me, imagining that I would end up with a series of essays on bachelorhood in 19th century American culture and, as sort of an exoskeleton, meta-reflections on the process of producing digital scholarship.

My first challenge was defining digital scholarship. The ACLS Commission on Cyberinfrastructure’s report points to five manifestations of digital scholarship: collection building, tools to support collection building, tools to support analysis, using tools and collections to produce “new intellectual products,” and authoring tools. Some might argue we shouldn’t really count tool and collection building as scholarship. I’ll engage with this question in more detail in a future post, but for now let me say that most consider critical editions, bibliographies, dictionaries and collations, arguably the collections and tools of the pre-digital era, to be scholarship. In many cases, building academic tools and collections requires significant research and expertise and results in the creation of knowledge—so, scholarship. Still, my primary focus is on the fourth aspect, leveraging digital resources and tools to produce new arguments. I’m realizing along the way, though, that I may need to build my own personal collections and develop my own analytical tools to do the kind of scholarship I want to do.

In a recent presentation at CNI, Tara McPherson, the editor of Vectors, offered her own “Typology of Digital Humanities”:

• The Computing Humanities: focused on building tools, infrastructure, standards and collections, e.g. The Blake Archive

• The Blogging Humanities: networked, peer-to-peer, e.g. crooked timber

• The Multimodal Humanities: “bring together databases, scholarly tools, networked writing, and peer-to-peer commentary while also leveraging the potential of the visual and aural media that so dominate contemporary life,” e.g. Vectors

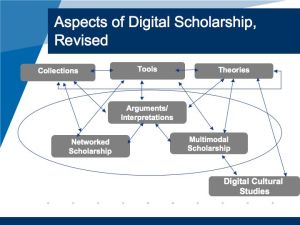

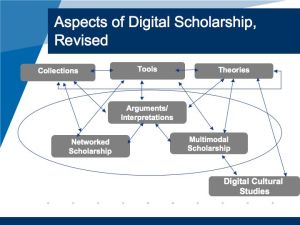

Mashing up these two frameworks, my own typology would look something like this:

• Tools, e.g. TAPOR, Zotero

• Collections, e.g. The Blake Archive

• Theories, e.g. McGann’s Radiant Textuality

• Interpretations and arguments that leverage digital collections and tools, e.g. Ayers and Thomas’ The Difference Slavery Made

• Networked Scholarship: a term that I borrow from the Institute for the Future of the Book’s Bob Stein and that I prefer to “blogging humanities,” since it encompasses many modes of communication, such as wikis, social bookmarking, institutional repositories, etc. Examples include Savage Minds (a group blog in anthropology), etc.

• Multimodal scholarship: e.g. scholarly hypertexts and videos, e.g. what you might find in Vectors

• Digital cultural studies, e.g. game studies, Lev Manovich’s work, etc (this category overlaps with theories)

Initially I assumed that tools, theories and collections would feed into arguments that would be expressed as networked and/or multimodal scholarship and be informed by digital cultural studies. But I think that describing digital scholarship as a sort of assembly line in which scholars use tools, collections and theories to produce arguments oversimplifies the process. My initial diagram of digital scholarship pictured single-headed arrows linking different approaches to digital scholarship; my revised diagram looks more like spaghetti, with arrows going all over the place. Theories inform collection building; the process of blogging helps to shape an argument; how a scholar wants to communicate an idea influences what tools are selected and how they are used.

After coming up with a preliminary definition of what I wanted to do, I needed to figure out how to structure my work. I thought of John Unsworth’s notion of scholarly primitives, a compelling description of core research practices. Depending on how you count them, Unsworth identifies 7 scholarly primitives:

• Discovering

• Annotating

• Comparing

• Referring

• Sampling

• Illustrating

• Representing

As useful as this list is in crystallizing what scholars do, I think the list is missing at least one more crucial scholarly primitive, perhaps the fundamental one: collaboration. Although humanists are stereotyped as solitary scholars isolated in the library, they often work together, whether through co-editing journals or books, sharing citations, or reviewing one another’s work. In the digital humanities, of course, developing tools, standards, and collections demands collaboration among scholars, librarians, programmers, etc. I would also define networked scholarship—blogging, contributing to wikis, etc—as collaborative, since it requires openly sharing ideas and supports conversation. It’s only appropriate for me to note that this idea was worked out collaboratively, with colleagues at THAT Camp.

I want to make my research process as visible as possible, not only for idealistic reasons, but also because my work only gets better the more feedback I receive. So I started up a blog—actually, several of them. At the somewhat grandly-named Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, I reflect on trends in the digital humanities and on broader lessons learned in the process of doing my research project. In “Lisa Spiro’s Research Notes,” I typically address stuff that seems too specialized, half-baked, or even raw for me to put on my main blog, such as my navel gazing on where to take my project next, or my experiments with Open Wound, a language re-mixing tool. At my PageFlakes research portal, I provide a single portal to the various parts of my research project, offering RSS feeds for both of my blogs as well as for a Google News search of the term “digital humanities,” my delicious bookmarks for “digital scholarship,” links to my various digital humanities projects, and more.

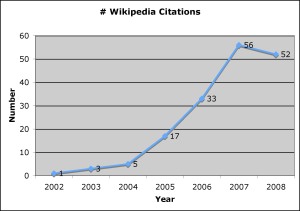

I’ll admit that when I started my experiments with social scholarship I worried that no one would care, or that I would embarrass myself by writing something really stupid, but so far I’ve loved the experience. Through comments and emails from readers, I’m able to see other perspectives and improve my own thinking. I’ve heard from biologists and anthropologists as well as literary scholars and historians, and I’ve communicated with researchers from several countries. As a result, I feel more engaged in the research community and more motivated to keep working. Although I know blogging hasn’t caught on in every corner of academia, I think it has been good for my career as a digital humanist. I am more visible and thus have more opportunities to participate in the community, such as by reviewing book proposals, articles, and grant applications.

I don’t have space to discuss the relevance of each scholarly primitive to my project, but I did want to mention a few of them: discovering, comparing, and representing.

Discovering

In order to use text analysis and other tools, I needed my research materials to be in an electronic format. In the age of mass digitization projects such as Google Books and the Open Content Alliance, I wondered how many of my 296 original research sources are digitized & available in full text. So I diligently searched Google Books and several other sources to find out. I looked at 5 categories: archival resources as well as primary and secondary books and journals. I found that with the exception of archival materials, over 90% of the materials I cited in my bibliography are in a digital format. However, only about 83% of primary resources and 37% of the secondary materials are available as full text. If you want to do use text analysis tools on 19th century American novels or 20th century articles from major humanities journals, you’re in luck, but the other stuff is trickier because of copyright constraints. (I’ll throw in another scholarly primitive, annotation, and say that I use Zotero to manage and annotate my research collections, which has made me much more efficient and allowed me to see patterns in my research collections.)

Of course, scholars need to be able to trust the authority of electronic resources. To evaluate quality, I focused on four collections that have a lot of content in my field, 19th century American literature: Google Books, Open Content Alliance, Early American Fiction (a commercial database developed by UVA’s Electronic Text Center), and Making of America. I found that there were some scanning errors with Google Books, but not as many as I expected. I wished that Google Books provided full text rather than PDF files of its public domain content, as do Open Content Alliance and Making of America (and EAF, if you just download the HTML). I had to convert Google’s PDF files to Adobe Tagged Text XML and got disappointing results. The OCR quality for Open Content Alliance was better, but words were not joined across line breaks, reducing accuracy. With multi-volume works, neither Open Content Alliance nor Google Books provided very good metadata. Still, I’m enough of a pragmatist to think that having access to this kind of data will enable us to conduct research across a much wider range of materials and use sophisticated tools to discern patterns – we just need to be aware of the limitations.

Comparing

To evaluate the power of text analysis tools for my project, I did some experiments using TAPOR tools, including a comparison of two of my key bachelor texts: Mitchell’s Reveries of a Bachelor, a series of a bachelor’s sentimental dreams (sometimes nightmares) about what it would be like to be married, and Melville’s Pierre, which mixes together elements of sentimental fiction, Gothic literature, and spiritualist tracts to produce a bitter satire. I wondered if there was a family resemblance between these texts. First I used the Wordle word cloud generator to reveal the most frequently appearing words. I noted some significant overlap, including words associated with family such as mother and father, those linked with the body such as hand and eye, and those associated with temporality, such as morning, night, and time. To develop a more precise understanding of how frequently terms appeared in the two texts and their relation to each other, I used TAPOR’s Comparator tool. This tool also revealed words unique to each work, such as “flirt” and “sensibility” in the case of Reveries, “ambiguities” and “miserable” in the case of Pierre. Finally, I used TAPOR’s concordance tool to view key terms in context. I found, for instance, that in Mitchell “mother” is often associated with hands or heart, while in Melville it appears with terms indicating anxiety or deceit. By abstracting out frequently occurring and unique words, I can how Melville, in a sense, remixes elements of sentimental fiction, putting terms in a darker context. The text analysis tools provide a powerful stimulus to interpretation.

Representing

Not only am I using the computer to analyze information, but also to represent my ideas in a more media-rich, interactive way than the typical print article. I plan to experiment with Sophie as a tool for authoring multimodal scholarship, and I’m also experimenting with video as a means for representing visual information. Right now I’m reworking an article on the publication history of Reveries of a Bachelor as a video so that I show significant visual information such as bindings, illustrations, and advertisements. I’ve condensed a 20+ page article into a 7 minute narrative, which for a prolix person like me is rough. I also have been challenged to think visually and cinematically, considering how the movement of the camera and the style of transitions shape the argument. Getting the right imagery—high quality, copyright free—has been tricky as well. I’m not sure how to bring scholarly practices such as citation into videos. Even though my draft video is, frankly, a little amateurish, putting it together has been lots of fun, and I see real potential for video to allow us to go beyond text and bring the human voice, music, movement and rich imagery into scholarly communication.

On Tools

In the course of my experiments in digital scholarship, I often found myself searching for the right tool to perform a certain task. Likewise, in my conversations with researchers who aren’t necessarily interested in doing digital scholarship, just in doing their research better, I learned that they weren’t aware of digital tools and didn’t know where to find out about them. To make it easier for researchers to discover relevant tools, I teamed up with 5 other librarians to launch the Digital Research Tools, or DiRT, wiki at the end of May. DiRT provides a directory of digital research tools, primarily free but also commercial, categorized by their functions, such as “manage citations.” We are also writing reviews of tools geared toward researchers and trying to provide examples of how these tools are used by the research community. Indeed, DiRT focuses on the needs of the community; the wiki evolves thanks to its contributors. Currently 14 people in fields such as anthropology, communications, and educational technology have signed on to be contributors. Everything is under a Creative Commons attribution license. We would love to see spin-offs, such as DiRT in languages besides English; DiRT for developers; and Old DiRT (dust?), the hall of obsolete but still compelling tools. My experiences with DiRT have demonstrated again the beauty of collaboration and sharing. Both Dan Cohen of CHNM & Alan Liu of UC Santa Barbara generously offered to let us grab content from their own tools directories. Busy folks have freely given their time to add tools to DiRT. Through my work on DiRT, I’ve learned about tools outside of my field, such as qualitative data analysis software.

So I’ll end with an invitation: Please contribute to DiRT. You can sign up to be an editor or reviewer, recommend tools to be added, or provide feedback via our survey. Through efforts like DiRT, we hope to enable new digital scholarship, raise the profile of inventive digital tools, and build community.