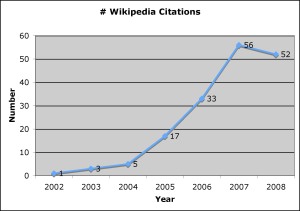

Last year a colleague in the English department described a conversation in which a friend revealed a dirty little secret: “I use Wikipedia all the time for my research—but I certainly wouldn’t cite it.” This got me wondering: How many humanities and social sciences researchers are discussing, using, and citing Wikipedia? To find out, I searched Project Muse and JSTOR, leading electronic journal collections for the humanities and social sciences, for the term “wikipedia,” which picked up both references to Wikipedia and citations of the wikipedia URL. I retrieved 167 results from between 2002 and 2008, all but 8 of which came from Project Muse. (JSTOR covers more journals and a wider range of disciplines but does not provide access to issues published in the last 3-5 years.) In contrast, Project Muse lists 149 results in a search for “Encyclopedia Britannica” between 2002 and 2008, and JSTOR lists 3. I found that citations of Wikipedia have been increasing steadily: from 1 in 2002 (not surprisingly, by Yochai Benkler) to 17 in 2005 to 56 in 2007. So far Wikipedia has been cited 52 times in 2008, and it’s only August.

Along with the increasing number of citations, another indicator that Wikipedia may be gaining respectability is its citation by well-known scholars. Indeed, several scholars both cite Wikipedia and are themselves subjects of Wikipedia entries, including Gayatri Spivak, Yochai Benkler, Hal Varian, Henry Jenkins, Jerome McGann, Lawrence Buell, and Donna Haraway.

111 of the sources (66.5%) are what I call “straight citations”—citations of Wikipedia without commentary about it–while 56 (34.5%) comment on Wikipedia as a source, either positively or negatively. 14.5% of the total citations come from literary studies, 14% from cultural studies, 11.4% from history, and 6.6% from law. Researchers cite Wikipedia on a diversity of topics, ranging from the military-industrial complex to horror films to Bush’s second state of the union speech. 8 use Wikipedia simply as a source for images (such as an advertisement for Yummy Mummy cereal or a diagram of the architecture of the Internet). Many employ Wikipedia either as a source for information about contemporary culture or as a reflection of contemporary cultural opinion. For instance, to illustrate how novels such as The Scarlet Letter and Uncle Tom’s Cabin have been sanctified as “Great American Novels,” Lawrence Buell cites the Wikipedia entry on “Great American Novel”(Buell).

About a third of the articles I looked at discuss the significance of Wikipedia itself. 14 (8%) criticize using it in research. For instance, a reviewer of a biography about Robert E. Lee tsks-tsks:

The only curiosities are several references to Wikipedia for information that could (and should) have been easily obtained elsewhere (battle casualties, for example). Hopefully this does not portend a trend toward normalizing this unreliable source, the very thing Pryor decries in others’ work. (Margolies).

In contrast, 11 (6.6%) cite Wikipedia as a model for participatory culture. For example:

The rise of the net offers a solution to the major impediment in the growth and complexification of the gift economy, that network of relationships where people come together to pursue public values. Wikipedia is one example.(DiZerega)

A few (1.8%) cite Wikipedia self-consciously, aware of its limitations but asserting its relevance for their particular project:

Citing Wikipedia is always dicey, but it is possible to cite a specific version of an entry. Start with the link here, because cybervandals have deleted the list on at least one occasion. For a reputable “permanent version” of “Alternative press (U.S. political right)” see: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alternative_press_%28U.S._political_right%29&oldid=107090129 (Berlet).

Of course, just because more researchers—including some prominent ones—are citing Wikipedia does not mean it’s necessarily a valid source for academic papers. However, you can begin to see academic norms shifting as more scholars find useful information in Wikipedia and begin to cite it. As Christine Borgman notes, “Scholarly documents achieve trustworthiness through a social process to assure readers that the document satisfies the quality norms of the field” (Borgman 84). As a possible sign of academic norms changing in some disciplines, several journals, particularly those focused on contemporary culture, include 3 or more articles that reference Wikipedia: Advertising and Society Review (7 citations), American Quarterly (3 citations), College Literature (3 citations), Computer Music Journal (5 citations), Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies (3 citations), Leonardo (8 citations), Library Trends (5 citations), Mediterranean Quarterly (3 citations), and Technology and Culture (3 citations).

So can Wikipedia be a reputable scholarly resource? I typically see four main criticisms of Wikipedia:

1) Research projects shouldn’t rely upon encyclopedias. Even Jimmy Wales, (co?-)founder of Wikipedia, acknowledges “I still would say that an encyclopedia is just not the kind of thing you would reference as a source in an academic paper. Particularly not an encyclopedia that could change instantly and not have a final vetting process” (Young). But an encyclopedia can be a valid starting point for research. Indeed, The Craft of Research, a classic guide to research, advises that researchers consult reference works such as encyclopedias to gain general knowledge about a topic and discover related works (80). Wikipedia covers topics often left out of traditional reference works, such as contemporary culture and technology. Most if not all of the works I looked at used Wikipedia to offer a particular piece of background information, not as a foundation for their argument.

2) Since Wikipedia is constantly undergoing revisions, it is too unstable to cite; what you read and verified today might be gone tomorrow–or even in an hour. True, but Wikipedia is developing the ability for a particular version of an entry to be vetted by experts and then frozen, so researchers could cite an authoritative, unchanging version (Young). As the above citation from Berlet indicates, you can already provide a link to a specific version of an article.

3) You can’t trust Wikipedia because anyone—including folks with no expertise, strong biases, or malicious (or silly) intent—can contribute to it anonymously. Yes, but through the back and forth between “passionate amateurs,” experts, and Wikipedia guardians protecting against vandals, good stuff often emerges. As Nicholson Baker, who has himself edited Wikipedia articles on topics such as the Brooklyn Heights and the painter Emma Fordyce MacRae, notes in a delightful essay about Wikipedia, “Wikipedia was the point of convergence for the self-taught and the expensively educated. The cranks had to consort with the mainstreamers and hash it all out” (Baker). As Roy Rosenzweig found in a detailed analysis of Wikipedia’s appropriateness for historical research, the quality of the collaboratively-produced Wikipedia entries can be uneven: certain topics are covered in greater detail than others, and the writing can have the choppy, flat quality of something composed by committee. But Rosenzweig also concluded that Wikipedia compares favorably with Encarta and Encyclopedia Britannica for accuracy and coverage.

4) Wikipedia entries lack authority because there’s no peer review. Well, depends on how you define “peer review.” Granted, Wikipedia articles aren’t reviewed by two or three (typically anonymous) experts in the field, so they may lack the scholarly authority of an article published in an academic journal. However, articles in Wikipedia can be reviewed and corrected by the entire community, including experts, knowledgeable amateurs, and others devoted to Wikipedia’s mission to develop, collect and disseminate educational content (as well as by vandals and fools, I’ll acknowledge). Wikipedia entries aim to achieve what Wikipedians call “verifiability”; the article about Barack Obama, for instance, has as many footnotes as a law review article–171 at last count (August 31), including several from this week.

Now I’m certainly not saying that Wikipedia is always a good source for an academic work–there is some dreck in it, as in other sources. Ultimately, I think Wikipedia’s appropriateness as an academic source depends on what is being cited and for what purpose. Alan Liu offers students a sensible set of guidelines for the appropriate use of Wikipedia, noting that it, like other encyclopedias, can be a good starting point, but that it is “currently an uneven resource” and always in flux. Instead of condemning Wikipedia outright, professors should help students develop what Henry Jenkins calls “new media literacies.” By examining the history and discussion pages associated with each article, for instance, students can gain insight into how knowledge is created and how to evaluate a source. As John Seely Brown and Richard Adler write:

The openness of Wikipedia is instructive in another way: by clicking on tabs that appear on every page, a user can easily review the history of any article as well as contributors’ ongoing discussion of and sometimes fierce debates around its content, which offer useful insights into the practices and standards of the community that is responsible for creating that entry in Wikipedia. (In some cases, Wikipedia articles start with initial contributions by passionate amateurs, followed by contributions from professional scholars/researchers who weigh in on the “final” versions. Here is where the contested part of the material becomes most usefully evident.) In this open environment, both the content and the process by which it is created are equally visible, thereby enabling a new kind of critical reading—almost a new form of literacy—that invites the reader to join in the consideration of what information is reliable and/or important.(Brown & Adler)

OK, maybe Wikipedia can be a legitimate source for student research papers–and furnish a way to teach research skills. But should it be cited in scholarly publications? In “A Note on Wikipedia as a Scholarly Source of Record,” part of the preface to Mechanisms, Matt Kirschenbaum offers a compelling explanation of why he cited Wikipedia, particularly when discussing technical documentation:

Information technology is among the most reliable content domains on Wikipedia, given the high interest of such topics Wikipedia’s readership and the consequent scrutiny they tend to attract. Moreover, the ability to examine page histories on Wikipedia allows a user to recover the editorial record of a particular entry… Attention to these editorial histories can help users exercise sound judgment as to whether or not the information before them at any given moment is controversial, and I have availed myself of that functionality when deciding whether or not to rely on Wikipedia.(Kirschenbaum xvii)

With Wikipedia, as with other sources, scholars should use critical judgment in analyzing its reliability and appropriateness for citation. If scholars carefully evaluate a Wikipedia article’s accuracy, I don’t think there should be any shame in citing it.

For more information, review the Zotero report detailing all of the works citing Wikipedia, or take a look at a spreadsheet of basic bibliographic information. I’d be happy to share my bibliographic data with anyone who is interested.

Works Cited

Baker, Nicholson. “The Charms of Wikipedia.” The New York Review of Books 55.4 (2008). 30 Aug 2008 <http://www.nybooks.com/articles/21131>.

Berlet, Chip. “The Write Stuff: U. S. Serial Print Culture from Conservatives out to Neonazis.” Library Trends 56.3 (2008): 570-600. 24 Aug 2008 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/library_trends/v056/56.3berlet.html>.

Booth, Wayne C, and Colomb, Gregory G. The Craft of Research. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2003.

Borgman, Christine L. Scholarship in the Digital Age: Information, Infrastructure, and the Internet. Cambridge, Mass., 2007.

Brown, John Seely, and Richard P. Adler. “Minds on Fire: Open Education, the Long Tail, and Learning 2.0 .” EDUCAUSE Review 43.1 (2008): 16-32. 29 Aug 2008 <http://connect.educause.edu/Library/EDUCAUSE+Review/MindsonFireOpenEducationt/45823?time=1220007552>.

Buell, Lawrence. “The Unkillable Dream of the Great American Novel: Moby-Dick as Test Case.” American Literary History 20.1 (2008): 132-155. 24 Aug 2008 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_literary_history/v020/20.1buell.pdf>.

Dee, Jonathan. “All the News That’s Fit to Print Out.” The New York Times 1 Jul 2007. 30 Aug 2008 <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/01/magazine/01WIKIPEDIA-t.html>.

DiZerega, Gus. “Civil Society, Philanthropy, and Institutions of Care.” The Good Society 15.1 (2006): 43-50. 24 Aug 2008 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/good_society/v015/15.1diZerega.html>.

Jenkins, Henry. “What Wikipedia Can Teach Us About the New Media Literacies (Part One).” Confessions of an Aca/Fan 26 Jun 2007. 30 Aug 2008 <http://www.henryjenkins.org/2007/06/what_wikipedia_can_teach_us_ab.html>.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Mechanisms : new media and the forensic imagination. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2008).

Liu, Alan. “Student Wikipedia Use Policy.” 1 Apr 2007. 30 Aug 2008 <http://www.english.ucsb.edu/faculty/ayliu/courses/wikipedia-policy.html>.

Margolies, Daniel S. “Robert E. Lee: Heroic, But Not the Polio Vaccine.” Reviews in American History 35.3 (2007): 385-392. 25 Aug 2008 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/reviews_in_american_history/v035/35.3margolies.html>.

Rosenzweig, Roy. “Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past.” The Journal of American History Volume 93, Number 1 (June, 2006): 117-46. Available at http://chnm.gmu.edu/resources/essays/d/42

Young, Jeffrey. “Wikipedia’s Co-Founder Wants to Make It More Useful to Academe.” Chronicle of Higher Education 13 Jun 2008. 28 Aug 2008 <http://chronicle.com/free/v54/i40/40a01801.htm?utm_source=at&utm_medium=en>.